One of the most iconic images of the 2022 FIFA World Cup qualifying is the picture of the Algerian coach Djamel Belmadi crouching on the ground in what was harrowing and gut-wrenching pain for him and his team who had just lost only their second match in 38 games and thus eliminated from the finals in Qatar later this year. This image served as a reminder of just how thin qualification margins are for the developing world especially in Africa, FIFA’s largest confederation by member associations. It’s unlikely that anyone with such a record would miss out on this quadrennial football fiesta. It further underlined why the system that governs the world football, the qualification and match organization goes against the very principles on which FIFA was found in 1904 i.e. the foundational principle of fair play. It painful reminder of an elusive dream for football’s developing world achieve fair play in how the game is governed. The system that was designed by and for the interest of the football superpowers i.e. the duopoly of UEFA (European Confederation) and CONMEBOL (the South American confederation) nearly a century continues to entrench and favour Europeans and South Americans and ensure that they exert undue influence and power on the affairs of global football and FIFA. Remarkably, another team Italy, had lost just 2 matches in 39 (of which only 1 was a world cup qualifier) and they too are not going to Qatar. But as you will see that is as far as the similarities go.

See, Italy unlike Algeria had 1 in 4 chances of making Qatar and two opportunities to make to do so i.e. the straight qualification by topping their qualifying group or a play-off route if they finish second. Algeria, however, had a little less than 1 in 10 chances of qualifying (with 5 slots for a confederation with 54 members) and only one shot at it. This is thanks to a qualifying slots allocation that gives European nations 13 of the 32 spaces while Africans get 5 of 32 finalists slots despite Africa like Europe making up a quarter of all FIFA member associations. The qualifying system put the injustice of the world football order in sharp focus. Of course, everyone who does not make it is gutted, but the World Cup slots allocation overwhelmingly favors European and South American nations at a 25% chance of qualifying and 45% chance of qualifying respectively. Not only is the dice stacked against the other regions, but the two also get protection from early eliminating in the finals tournament thanks to a seeding system. This gives European and South American a double advantage of being able to send more finalist s than the fair share and an systematic protection again early elimination. A study by James Monks and Jared Husch first published in 2009 on the impact of seeding on results found that playing in one’s continent and being seeded increases one’s chances of advancing to the quarter-finals by 12% and 26% respectively. Such is the South America and European stranglehold on this, according to FIFA records, Cuba is the only non-host ever seeded in the history of the World Cup way back in 1938 (by the decision of the organizing committee) from outside South America and Europe. Qatar became only the 6th nation to be seeded (as host) from outside the duopoly joining Mexico (2), the USA, Korea, Japan, and South Africa. Imagine if the FIFA World Cup like the oldest competition, the FA Cup, had an open draw rather than the seeded system. Imagine if the World Cup slot allocation is based on the membership size.

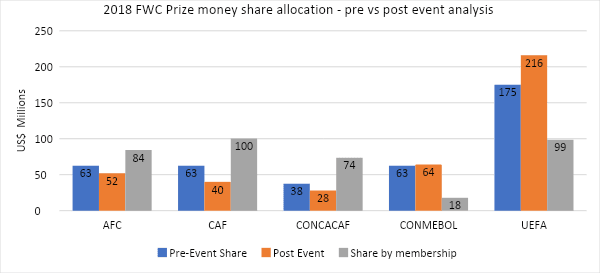

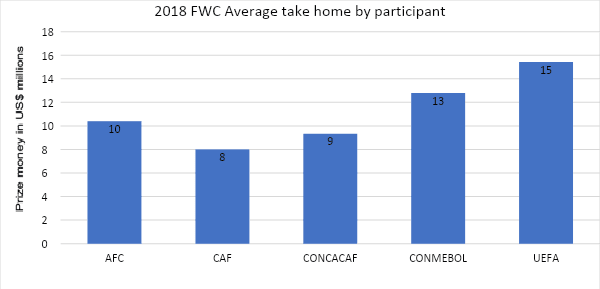

Perhaps if this is where the unfairness ended, one would accept this as an anomaly, it gets worse. The format leads to better chances and results which delivers rich rewards in commercials, incentives, and prize money. Here is the economic impact of this practice and how it shapes the economic fortunes of the game, again, in favor of the Europeans and South Americans. In 2018, during the FIFA World Cup, the total prize pool distributed was US$400. The two graphs below show the impact of the economic impact of this injustice. The first graph shows three sets of numbers. The first looks at what the share of each region would be if FIFA were to split the money equally amounts to all the 32 participants and the winner will get the trophy and will be world champions but everyone gets the same. Each participant would walk away with US$12.5m. These numbers are the bar titled pre-event equal share. The second is post-event actual allocation based on the results and it shows that while Europe’s equitable share on the above basis is 44%, they walked away 54% of the pot. Everybody else except South America walks away with less than they would have, had they decided to just split the money equally. The last bar graph is self-explanatory. If this prize money was shared by regional membership size, Africa will get the most at $100m. The second graph is also a simple illustration and shows the. result of oversized qualification chances and seeding, they walked away with the most. On average, the European qualifier walks home with $15m per team nearly twice what the average African participants get at $8m.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

What is the point of all of this? Why make these meaningless comparisons? Well, I will go back to where it all started the foundational principle of fair play and the rules that govern the game are based on the fundamental principle of eliminating any artificial subjectivity and ensuring the leveling of the playing field in how the key decisions in the game are made. To this day at the start of the match, the coin toss is a fair way of deciding who takes the kick-off and who picks the goal to defend? At penalty shoot outs, who kicks the first penalty or saves one, are all decided by a fair unmanipulable coin toss. The concepts of relative regional strength that informed the differences in slot allocation and the seeding system arising from that go against this principle of fair play. How is it fair to take 32 teams and to select some that cannot be eliminated early or play each other in the tournament, to effectively fix what matchups can happen and which cannot happen, how is it fair play to advance a system that quite clearly gives some artificially chosen teams a 26% more chance of advancing while other do not?

As we look at the picture of the Algerian coach’s pain we cannot do so without seeing the unfairness and the injustice created by systematically favouring and entrenching some at the expense of others. It is time the game lives up to its founding principles of fair play and advancing equitable opportunities for all its members and that starts with removing the status of some as first-class and other second-class members afforded to South Americans and Europeans. The performance of African nations over the last couple of tournaments has been unhelpful to Africa’s cause but that cannot be used to justify thus continue injustice. The good news is that the developing world has the numbers to make these changes. Whether or not they will is another matter. The reality, however, is that the change to advance the game for the world and its unparalleled socio-economic and political role in society, is long overdue.